This started the way a lot of physics discoveries do. With confusion.

Researchers running routine experiments noticed magnetic signals that didn’t line up with existing models. The oscillations were real. They were repeatable. And they didn’t fit neatly into anything already on the books.

At first, the assumption was error. Calibration issues. Noise. Something mundane.

It wasn’t.

After months of checking and rechecking, physicists now say they’ve identified a strange new class of magnetic oscillation states that behave in ways conventional magnetism does not predict. The finding is early, still being debated, but it’s already forcing theorists to slow down and rethink a few assumptions.

That’s where things get interesting.

What physicists expected, and what they saw instead

In most magnetic systems, oscillations follow fairly predictable rules. Apply a magnetic field, change the temperature, adjust the material’s structure, and the response follows known patterns.

These new states don’t.

The oscillations appear to switch modes spontaneously, sometimes locking into stable rhythms and other times drifting without an obvious trigger. In some cases, the magnetic response seems to depend not just on current conditions, but on the system’s recent history.

That may sound abstract, but it’s unusual.

Magnetism is usually well-behaved. This is not.

The materials at the center of the discovery

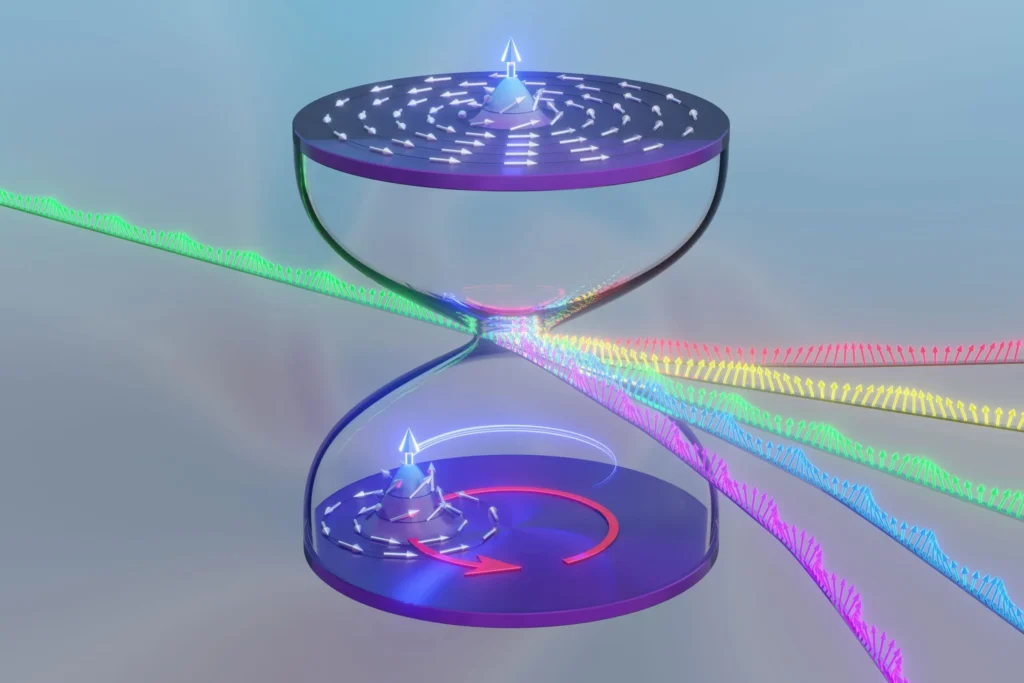

The experiments were conducted on complex quantum materials, often layered or strongly correlated systems where electrons interact intensely with each other.

These materials are already known for surprises. Superconductivity. Exotic phases. Unusual electrical behavior.

Still, even by those standards, the newly observed magnetic oscillations stand out.

The key appears to be how spins interact collectively. Instead of settling into a single pattern, the spins enter oscillatory states that persist without external driving forces.

In simple terms, the system keeps wobbling on its own.

That’s not something classical magnetism expects.

Why these oscillations are considered “bizarre”

The word bizarre gets overused in science headlines, but here it’s doing some real work.

The oscillations don’t fade the way damped systems usually do. They don’t require continuous energy input. And they don’t always repeat the same way when experiments are restarted.

In some tests, slight changes produced radically different outcomes. In others, big changes did almost nothing.

This kind of sensitivity suggests the system sits near a boundary between multiple states. Small nudges push it one way or another.

Physicists call this kind of behavior emergent. Meaning it arises from collective interactions, not from any single particle acting strangely.

What theories are being floated so far

Right now, explanations are tentative.

Some researchers point to non-equilibrium quantum effects, where the system never fully settles into a stable state. Others suspect new forms of spin coupling that haven’t been fully explored.

There’s also discussion around whether these oscillations represent an entirely new magnetic phase, rather than a quirk of known ones.

That distinction matters more than it sounds.

If this is a new phase, it could reshape how scientists classify magnetic materials. If it’s a transient effect, it may still open doors to new ways of controlling magnetism.

Either way, theorists are busy.

Why this matters beyond pure curiosity

It’s fair to ask what any of this means outside a physics lab.

For now, there are no immediate applications. Nobody is claiming this will power devices next year.

But magnetic behavior underpins a lot of modern technology. Data storage. Sensors. Quantum computing components. Spin-based electronics.

Systems that oscillate without constant energy input are especially intriguing. They hint at more efficient ways to maintain signals or states, which is a constant challenge in advanced electronics.

Early signs suggest these oscillations could be tuned or controlled with the right material engineering. That’s a big if, but it’s enough to keep applied physicists paying attention.

A reminder of how incomplete our understanding still is

Magnetism is one of the oldest studied phenomena in physics. Compasses existed long before equations did.

And yet, here we are.

New magnetic behavior showing up in materials that didn’t even exist a few decades ago. Behavior that slips through existing theories and forces new ones to be built.

This part matters more than it sounds.

It’s easy to assume foundational sciences are finished. That all the big discoveries are behind us. Findings like this quietly push back against that idea.

What happens next is slower than headlines suggest

Don’t expect instant consensus.

Other labs will try to reproduce the results. Some will succeed. Others may not. Measurements will be refined. Alternative explanations will be tested.

This process takes time. Sometimes years.

If the oscillations hold up across different materials and setups, they’ll move from curiosity to category. If not, they’ll still leave behind better tools and sharper questions.

That’s how physics tends to move forward.

A discovery that raises more questions than answers

For now, the most honest takeaway is uncertainty.

Physicists have observed something real. Something repeatable. Something not fully understood.

Whether these bizarre magnetic oscillation states become a footnote or a foundational concept will depend on what comes next.

But moments like this are a reminder of why experimental science still matters. Even in well-mapped territory, nature finds ways to surprise us.

And when it does, the real work begins.